African History

Collection

A collection of data on the history of mankind

•

12 items

•

Updated

•

3

title

stringlengths 29

135

| description

stringlengths 1

424

| url

stringlengths 67

81

| content

stringlengths 1.84k

55.5k

| publishedTime

stringlengths 25

25

| usage

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

a brief note on contacts between ancient African kingdoms and Rome. | finding the lost city of Rhapta on the east African coast. | https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-contacts-between | Few classical civilizations were as impactful to the foreign contacts of ancient African states and societies like the Roman Empire.

Shortly after Augustus became emperor of Rome, his armies undertook a series of campaigns into the African mainland south of the Mediterranean coast. The first of the Roman campaigns was directed into Nubia around 25BC, [but was defeated by the armies of Kush in 22BC](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-meroitic-empire-queen-amanirenas). While the Roman defeat in Nubia permanently ended its ambitions in this region and was concluded with a treaty between Kush's envoys and the emperor on the Greek island Samos in 21BC, Roman campaigns into central Libya beginning in 20BC were relatively successful and the region was gradually incorporated into the empire.

The succeeding era, which is often referred to as '_Pax Romana_', was a dynamic period of trade and cultural exchanges between Rome and the rest of the world, including north-eastern Africa and the Indian Ocean world.

The increase in commercial and diplomatic exchanges between Kush and Roman Egypt contributed to the expansion of the economy of Meroitic Kush, which was one of the sources of gold and ivory exported to Meditteranean markets.[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-contacts-between#footnote-1-145467894) By the 1st century CE, Meroe had entered a period of prosperity, with monumental building activity across the cities of the kingdom, as well as a high level of intellectual and artistic production. [The appearance of envoys from Meroe and Roman Egypt in the documentary record of both regions](https://www.patreon.com/posts/africans-in-rome-75714077) demonstrates the close relationship between the two state’s diplomatic and economic interests.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ffeff442e-413c-48ef-9ce1-434a670fece3_705x517.png)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fbc02237f-7fef-439d-9587-0ecb3514de08_640x433.png)

_**the shrine of Hathor (also called the 'Roman kiosk') at Naqa, Sudan. ca. 1st century CE**_.

_It was constructed by the Meroitic co-rulers Natakamani and Amanitore and served as a ‘transitory’ shrine in front of the larger temple of the Nubian god Apedemak (seen in the background). Its nickname is derived from its mix of Meroitic architecture (like the style used for the Apedemak temple) with Classical elements (like the decoration of the shrine’s columns and arched windows). The Meroitic inscriptions found on the walls of the shrine indicate that it was built by local masons who were likely familiar with aspects of the construction styles of Roman-Egypt or assisted by a few masons from the latter._[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-contacts-between#footnote-2-145467894)

[Share](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-contacts-between?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email&utm_content=share&action=share)

The patterns of exchange and trade that characterized _Pax Romana_ would also contribute to the expansion of Aksumite commercial and political activities in the Red Sea region, which was a conduit for the lucrative trade in silk and spices from the Indian Ocean world as well as ivory from the Aksumite hinterland. At the close of the 2nd century, the armies of Aksum were campaigning on the Arabian peninsula and the kingdom’s port city of Adulis had become an important anchorage for merchant ships traveling from Roman-Egypt to the Indian Ocean littoral. These activities would lay the foundation for the success of [Aksumite merchants as intermediaries in the trade between India and Rome](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-aksumite-empire-between-rome).

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8bf2919f-6977-4011-a801-9fcc425c13be_794x447.gif)

_**Dungur Palace, Aksum, Ethiopia - Reconstruction, by World History Encyclopedia.**_

_This large, multi-story complex was one of several structures that dominated the Aksumite capital and regional towns across the kingdom, and its architectural style was a product of centuries of local developments. The material culture of these elite houses indicates that their occupants had access to luxury goods imported from Rome, including glassware, amphorae, and Roman coins._[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-contacts-between#footnote-3-145467894)

The significance of the relationship between Rome and the kingdoms of Kush and Aksum can be gleaned from Roman accounts of world geography in which the cities of Meroe and Aksum are each considered to be a '_**Metropolis**_' —a term reserved for large political and commercial capitals. This term had been used for Meroe since the 5th century BC and Aksum since the 1st century CE, since they were the largest African cities known to the classical writers[4](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-contacts-between#footnote-4-145467894).

However, by the time Ptolemy composed his monumental work on world geography in 150 CE, another African city had been elevated to the status of a Metropolis. This new African metropolis was the **city of Rhapta,** located on the coast of East Africa known as _‘Azania’_, and it was the southernmost center of trade in a chain of port towns that stretched from the eastern coast of Somalia to the northern coast of Mozambique.

**The history of the ancient East African coast and its links to the Roman world are the subject of my latest Patreon article.**

**Please subscribe to read about it here:**

[ANCIENT EAST AFRICA AND THE ROMANS](https://www.patreon.com/posts/105868178)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa02dc2b6-500a-4e26-bafe-28947296eeef_1102x623.png)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F361130f0-63cc-4739-ba0e-841ca6726865_820x704.png)

_**Fresco with an aithiopian woman presenting ivory to a seated figure (Dido of Carthage) as a personified Africa overlooks**_, from House of Meleager at Pompeii, MAN Napoli 8898, Museo Archaeologico Nazionale, Naples | 2024-06-09T16:20:45+00:00 | {

"tokens": 2097

} |

A complete history of Abomey: capital of Dahomey (ca. 1650-1894) | Journal of African cities chapter 10. | https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital | Abomey was one of the largest cities in the "forest region" of west-Africa; a broad belt of kingdoms extending from Ivory coast to southern Nigeria. Like many of the urban settlements in the region whose settlement was associated with royal power, the city of Abomey served as the capital of the kingdom of Dahomey.

Home to an estimated 30,000 inhabitants at its height in the mid-19th century, the walled city of Abomey was the political and religious center of the kingdom. Inside its walls was a vast royal palace complex, dozens of temples and residential quarters occupied by specialist craftsmen who made the kingdom's iconic artworks.

This article outlines the history of Abomey from its founding in the 17th century to the fall of Dahomey in 1894.

**Map of modern benin showing Abomey and other cities in the kingdom of Dahomey.[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-1-136876141)**

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F15e9b90d-c29e-44ee-9d7e-ee851cd2300c_846x481.png)

**Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this blog free for all:**

[PATREON](https://www.patreon.com/isaacsamuel64)

**The early history of Abomey: from the ancient town of Sodohome to the founding of Dahomey’s capital.**

The plateau region of southern Benin was home to a number of small-scale complex societies prior to the founding of Dahomey and its capital. Like in other parts of west-Africa, urbanism in this region was part of the diverse settlement patterns which predated the emergence of centralized states. The Abomey plateau was home to several nucleated iron-age settlements since the 1st millennium BC, many of which flourished during the early 2nd millennium. The largest of these early urban settlements was Sodohome, an ancient iron age dated to the 6th century BC which at its peak in the 11th century, housed an estimated 5,700 inhabitants. Sodohome was part of a regional cluster of towns in southern Benin that were centers of iron production and trade, making an estimated 20 tonnes of iron each year in the 15th/16th century.[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-2-136876141)

The early settlement at Abomey was likely established at the very founding of Dahomey and the construction of the first Kings' residences. Traditions recorded in the 18th century attribute the city's creation to the Dahomey founder chief Dakodonu (d. 1645) who reportedly captured the area that became the city of Abomey after defeating a local chieftain named Dan using a _Kpatin_ tree. Other accounts attribute Abomey's founding to Houegbadja the "first" king of Dahomey (r. 1645-1685) who suceeded Dakodonu. Houegbadja's palace at Abomey, which is called _Kpatissa_, (under the kpatin tree), is the oldest surviving royal residence in the complex and was built following preexisting architectural styles.[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-3-136876141)

(read more about [Dahomey’s history in my previous article on the kingdom](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-kingdom-of-dahomey-and-the-atlantic))

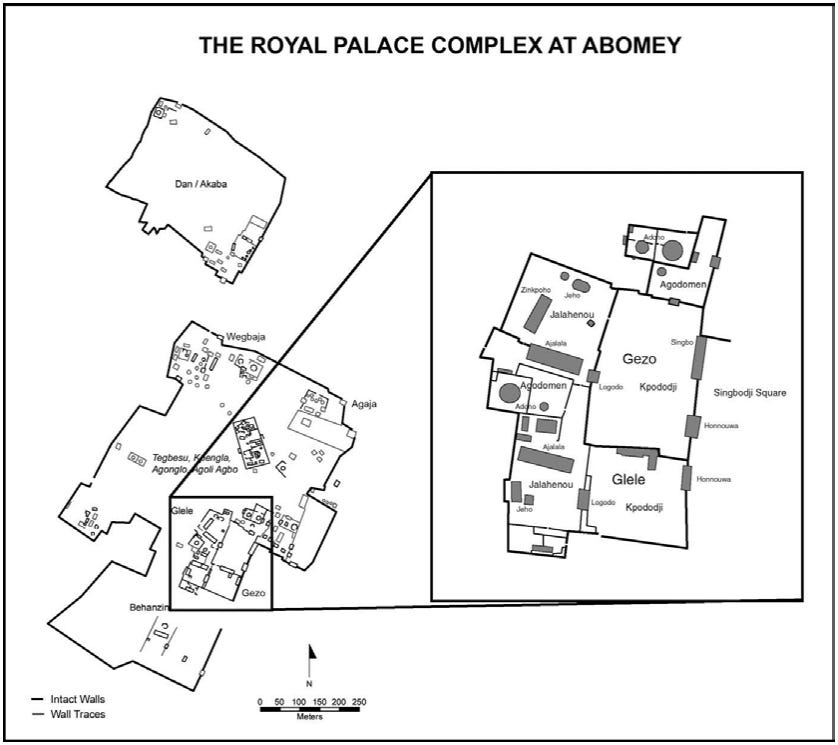

The pre-existing royal residences of the rulers who preceeded Dahomey’s kings likely included a _hounwa_ (entrance hall) and an _ajalala_ (reception hall), flanked by an _adoxo_ (tomb) of the deceased ruler. The palace of Dan (called _Dan-Home_) which his sucessor, King Houegbadja (or his son) took over, likely followed this basic architectural plan. Houegbadja was suceeded by Akaba (r. 1685-1708) who constructed his palace slightly outside what would later become the palace complex. In addition to the primary features, it included two large courtyards; the _kpododji_ (initial courtyard), an _ajalalahennu_ (inner/second courtyard), a _djeho_ (soul-house) and a large two-story building built by Akaba's sucessor; Agaja.[4](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-4-136876141)

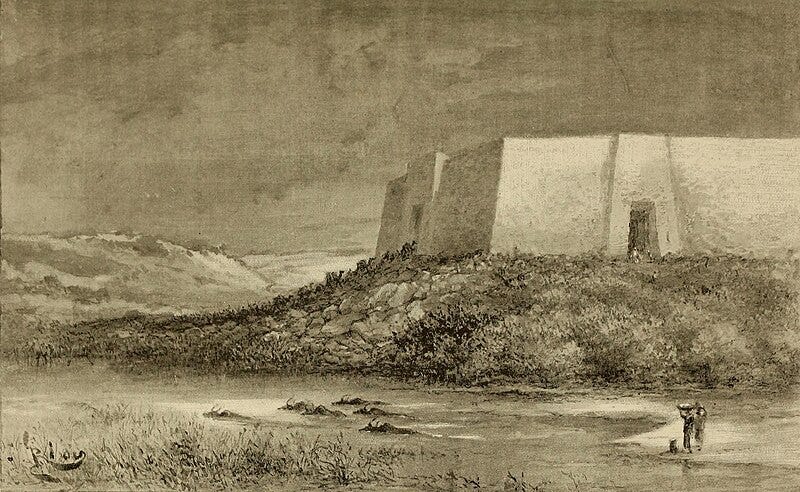

Agaja greatly expanded the kingdom's borders beyond the vicinity of the capital. After nearly a century of expansion and consolidation by his predecessors across the Abomey Plateau, Agaja's armies marched south and captured the kingdoms of Allada in 1724 and Hueda in 1727. In this complex series of interstate battles, Abomey was sacked by Oyo's armies in 1726, and Agaja begun a reconstruction program to restore the old palaces, formalize the city's layout (palaces, roads, public spaces, markets, quarters) and build a defensive system of walls and moats. The capital of Dahomey thus acquired its name of Agbomey (Abomey = inside the moat) during Agaja's reign.[5](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-5-136876141)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Feeb6450f-b9df-4165-a9de-1a2a4f1d71eb_898x431.png)

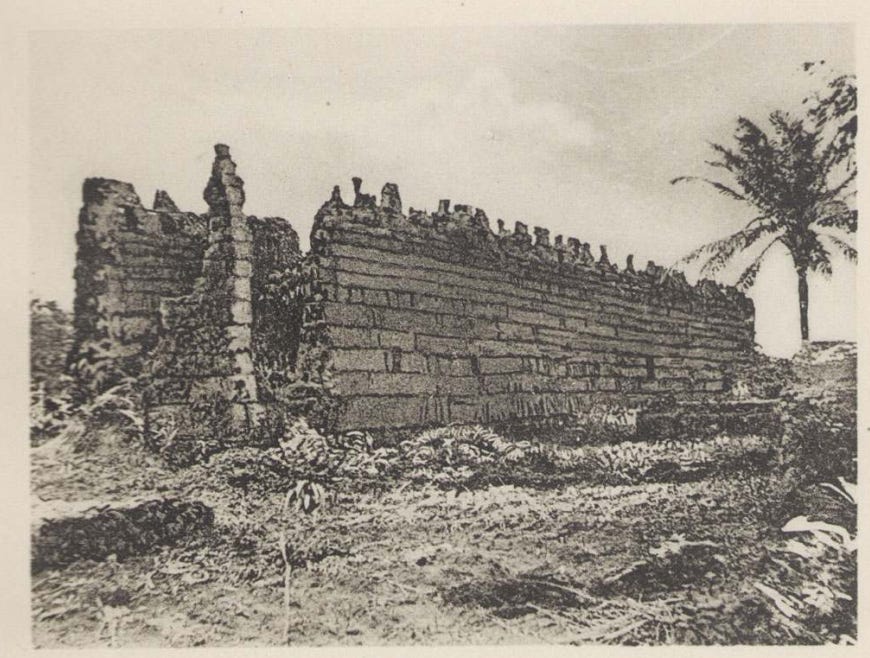

Ruins of an unidentified palace in Abomey, ca. 1894-1902. Quai branly most likely to be the simbodji palace of Gezo.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8d3f1332-6516-4d52-bcf2-57df3e78fb8c_893x573.jpeg)

_**Section of the Abomey Palace complex in 1895**_, Quai branly.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6929ad14-36cd-4e60-875e-fd72d0ce2a70_838x745.png)

The royal palace complex at Abomey, map by J. C. Monroe

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fea838214-b87e-4e86-926e-5d0ce5006918_870x658.png)

_**Section of the ruined palace of Agaja**_ in 1911. The double-storey structure was built next to the palace of Akaba

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fbc8eec93-993c-47c1-a4f9-9a08a01d5111_745x546.png)

_**Section of Agaja’s palace**_ in 1925, Quai branly.

[Share](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email&utm_content=share&action=share)

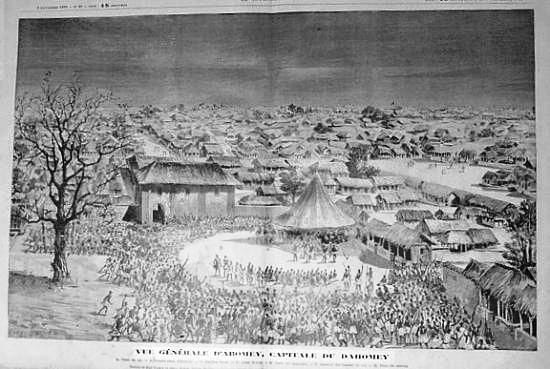

**The royal capital of Abomey during the early 18th century**

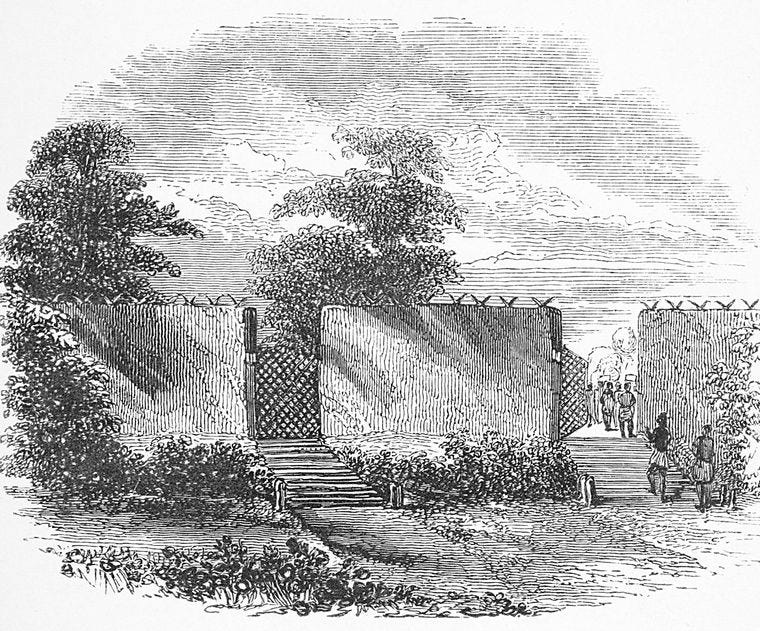

The administration of Dahomey occurred within and around a series of royal palace sites that materialized the various domestic, ritual, political, and economic activities of the royal elite at Abomey. The Abomey palace complex alone comprised about a dozen royal residences as well as many auxiliary buildings. Such palace complexes were also built in other the regional capitals across the kingdom, with as many as 18 palaces across 12 towns being built between the 17th and 19th century of which Abomey was the largest. By the late 19th century, Abomey's palace complex covered over a hundred acres, surrounded by a massive city wall about 30ft tall extending over 2.5 miles.[6](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-6-136876141)

These structures served as residences for the king and his dependents, who numbered 2-8,000 at Abomey alone. Their interior courtyards served as stages on which powerful courtiers vied to tip the balance of royal favor in their direction. Agaja's two story palace near the palace of Akba, and his own two-story palace within the royal complex next to Houegbadja's, exemplified the centrality of Abomey and its palaces in royal continuity and legitimation. Sections of the palaces were decorated with paintings and bas-reliefs, which were transformed by each suceeding king into an elaborate system of royal "communication" along with other visual arts.[7](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-7-136876141)

Abomey grew outwardly from the palace complex into the outlying areas, and was organized into quarters delimited by the square city-wall.[8](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-8-136876141) Some of the quarters grew around the private palaces of the kings, which were the residences of each crown-prince before they took the throne. Added to these were the quarters occupied by the guilds/familes such as; blacksmiths (Houtondji), artists (Yemadji), weavers, masons, soldiers, merchants, etc. These palace quarters include Agaja's at Zassa, Tegbesu’s at Adandokpodji, Kpengla’s at Hodja, Agonglo’s at Gbècon Hwégbo, Gezo’s at Gbècon Hunli, Glele's at Djègbè and Behanzin's at Djime.[9](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-9-136876141)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fcf46c7f9-85a3-4e65-ad6b-581dca1d772c_550x369.jpeg)

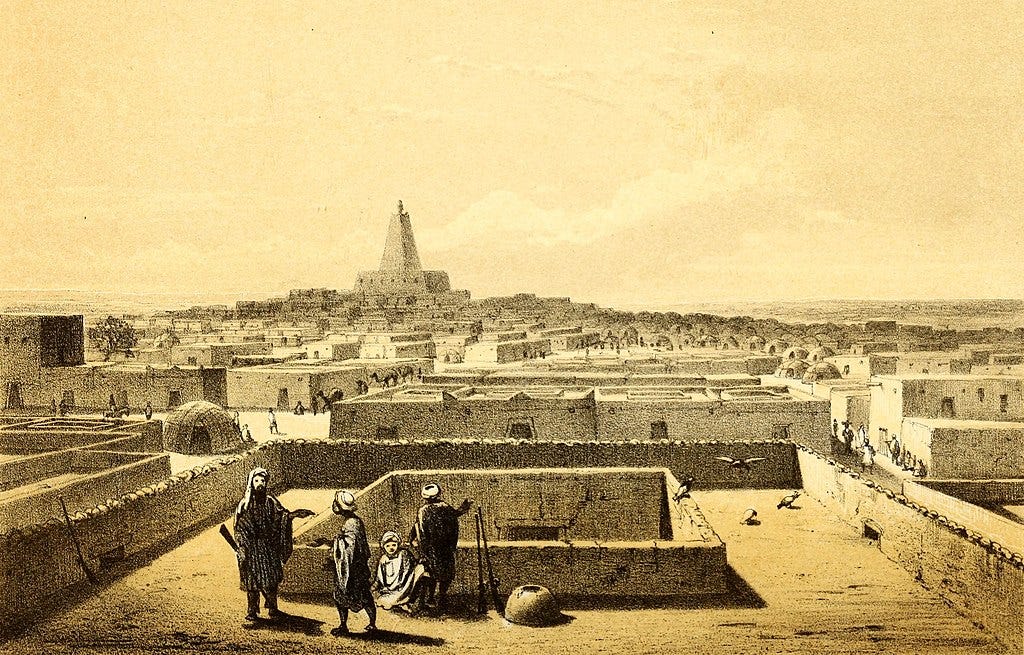

_**illustration of Abomey in the 19th century**_.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff7e86a41-0314-4b04-9e0c-3d471ed79b8f_760x631.jpeg)

_**illustration of Abomey’s city gates and walls**_, ca. 1851

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7cc5e89b-a951-4dab-9dc6-89fcb44d3b6c_600x421.jpeg)

_**interior section in the ‘private palace’ of Prince Aho Gléglé (grandson of Glele)**_, Abomey, ca. 1930, Archives nationales d'outre-mer

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4e1c90a3-86fa-488a-bb9b-f064fff70728_890x562.png)

_**Tomb of Behanzin in Abomey**_, early 20th century, Imagesdefence, built with the characteristic low hanging steep roof.

**Abomey in the late 18th century: Religion, industry and art.**

Between the end of Agaja's reign and the beginning of Tegbesu's, Dahomey became a tributary of the Oyo empire (in south-western Nigeria), paying annual tribute at the city of Cana. In the seven decades of Oyo's suzeranity over Dahomey, Abomey gradually lost its function as the main administrative capital, but retained its importance as a major urban center in the kingdom. The kings of this period; Tegbesu (r. 1740-1774), Kpengla (r. 1774-1789) and Agonglo (r. 1789-1797) resided in Agadja’s palace in Abomey, while constructing individual palaces at Cana. But each added their own entrance and reception halls, as well as their own honga (third courtyard).[10](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-10-136876141)

Abomey continued to flourish as a major center of religion, arts and crafts production. The city's population grew by a combination of natural increase from established families, as well as the resettlement of dependents and skilled artisans that served the royal court. Significant among these non-royal inhabitants of Dahomey were the communities of priests/diviners, smiths, and artists whose work depended on royal patronage.

The religion of Dahomey centered on the worship of thousands of vodun (deities) who inhabited the Kutome (land of the dead) which mirrored and influenced the world of the living. Some of these deities were localized (including deified ancestors belonging to the lineages), some were national (including deified royal ancestors) and others were transnational; (shared/foreign deities like creator vodun, Mawu and Lisa, the iron and war god Gu, the trickster god Legba, the python god Dangbe, the earth and health deity Sakpata, etc).[11](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-11-136876141)

Each congregation of vodun was directed by a pair of priests, the most influencial of whom were found in Abomey and Cana. These included practitioners of the cult of tohosu that was introduced in Tegbesu's reign. Closely associated with the royal family and active participants in court politics, Tohosu priests built temples in Abomey alongside prexisting temples like those of Mawu and Lisa, as well as the shrines dedicated to divination systems such as the Fa (Ifa of Yoruba country). The various temples of Abomey, with their elaborated decorated facades and elegantly clad tohosu priests were thus a visible feature of the city's architecture and its function as a religious center.[12](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-12-136876141)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fffc11894-eae0-4c16-8c34-456ba34fb482_878x586.jpeg)

_**Temple courtyard dedicated to Gu in the palace ground of king Gezo**_, ca. 1900, library of congress

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F87ab0fa6-05cb-48a7-9d23-6915f5d975f7_833x573.jpeg)

_**entrance to the temple of Dangbe**_, Abomey, ca. 1945, Quai branly (the original roofing was replaced)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc69820b6-88f0-4f45-b52c-2d77df1608c6_1024x555.png)

_**Practicioners of Gu and Tohusu**_ _**in Abomey**_, ca. 1950, Quai branly

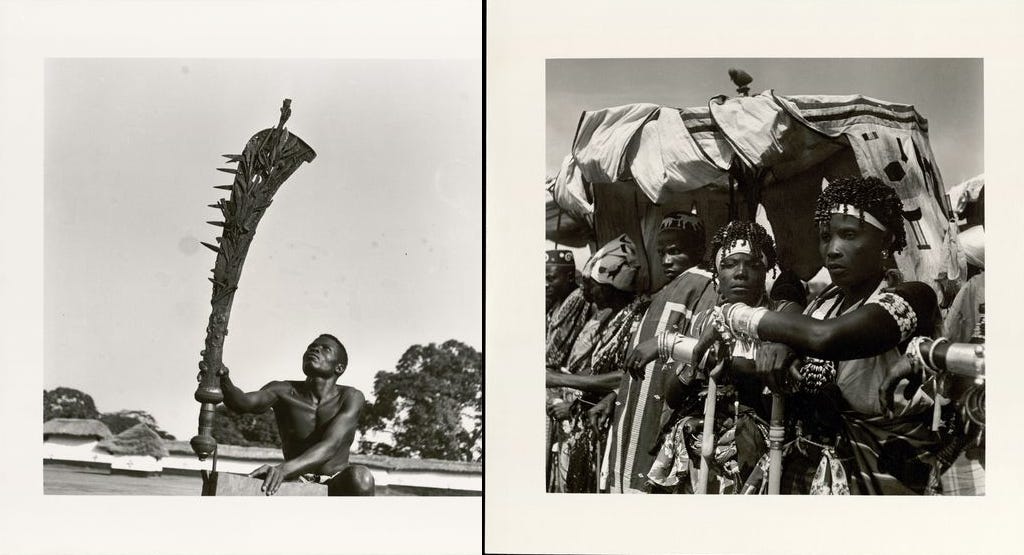

Besides the communities of priests were the groups of craftsmen such as the Hountondji families of smiths. These were originally settled at Cana in the 18th century and expanded into Abomey in the early 19th century, setting in the city quarter named after them. They were expert silversmiths, goldsmiths and blacksmiths who supplied the royal court with the abundance of ornaments and jewelery described in external accounts about Abomey. Such was their demand that their family head, Kpahissou was given a prestigious royal title due to his followers' ability to make any item both local and foreign including; guns, swords and a wheeled carriage described as a "square with four glass windows on wheels".[13](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-13-136876141)

The settlement of specialist groups such as the Hountondji was a feature of Abomey's urban layout. Such craftsmen and artists were commisioned to create the various objects of royal regalia including the iconic thrones, carved doors, zoomorphic statues, 'Asen' sculptures, musical instruments and figures of deities. Occupying a similar hierachy as the smiths were the weavers and embroiderers who made Dahomey's iconic textiles.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7f302bff-c74c-4030-9f3c-959d5f837438_836x573.jpeg)

Carved blade from 19th century Abomey, Quai branly. made by the Hountondji smiths.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7dd017eb-29d0-4942-bb64-3aecd428e931_764x573.jpeg)

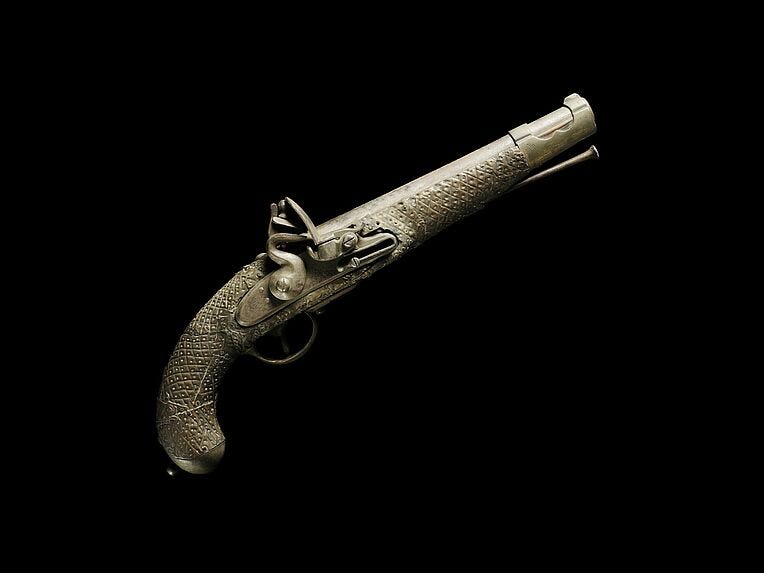

_**Pistol modified with copper-alloy plates**_, 1892, made by the Hountondji smiths.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1f803d6b-48dd-4fe5-baab-d11df08780a6_1029x618.png)

_**Asen staff from Ouidah**_, mid-19th cent., Musée Barbier-Mueller, _**Hunter and Dog with man spearing a leopard**_, ca. 1934, Abomey museum. _**Brass sculpture of a royal procession**_, ca 1931, Fowler museum

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe83c8cb2-0a79-47da-99f4-b452b320a3c2_1134x499.png)

Collection of old jewelery and Asen staffs in the Abomey museum, photos from 1944.

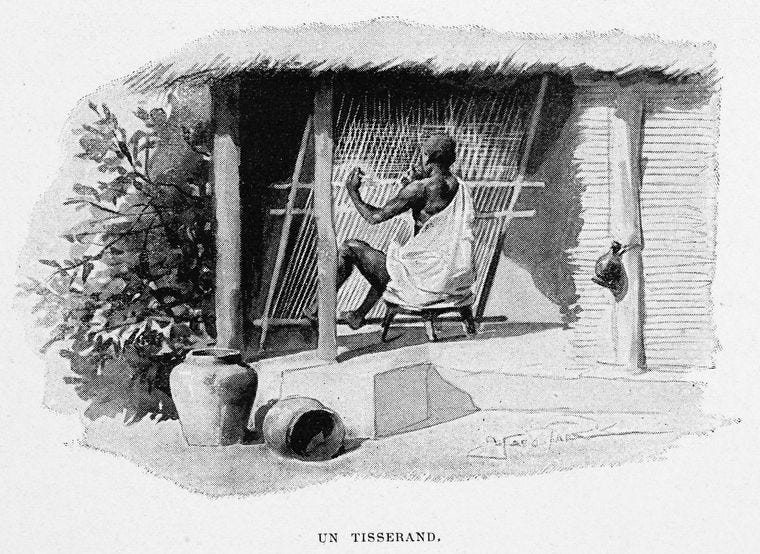

Cloth making in Abomey was part of the broader textile producing region and is likely to have predated the kingdom's founding. But applique textiles of which Abomey is famous was a uniquely Dahomean invention dated to around the early 18th century reign of Agadja, who is said to have borrowed the idea from vodun practitioners. Specialist families of embroiders, primarily the Yemaje, the Hantan and the Zinflu, entered the service of various kings, notably Gezo and Glele, and resided in the Azali quarter, while most cloth weavers reside in the gbekon houegbo.[14](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-14-136876141)

The picto-ideograms depicted on the applique cloths that portray figures of animals, objects and humans, are cut of plain weave cotton and sewn to a cotton fabric background. They depict particular kings, their "strong names" (royal name), their great achievements, and notable historical events. The appliques were primary used as wall hangings decorating the interior of elite buildings but also featured on other cloth items and hammocks. Applique motifs were part of a shared media of Dahomey's visual arts that are featured on wall paintings, makpo (scepters), carved gourds and the palace bas-reliefs.[15](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-15-136876141) Red and crimson were the preferred colour of self-representation by Dahomey's elite (and thus its subjects), while enemies were depicted as white, pink, or dark-blue (all often with scarifications associated with Dahomey’s foe: the Yoruba of Oyo).[16](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-16-136876141)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1029ab69-2981-496f-bd97-139949fece38_760x554.jpeg)

_**Illustration showing a weaver at their loom in Abomey**_, ca. 1851

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F80a525c4-7951-437c-9af5-0db933d902ff_787x572.png)

_**Cotton tunics from Abomey, 19th century**_, Quai branly. The second includes a red figure in profile.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F613e0ca3-cc26-4ec8-9d29-ea0362fb0649_1027x507.png)

_**Applique cloths from Abomey depicting war scenes**_, _**Quai branly**_. Both show Dahomey soldiers (in crimson with guns) attacking and capturing enemy soldiers (in dark blue/pink with facial scarification). The first is dated to 1856, and the second is from the mid-20th cent.

The bas-reliefs of Dahomey are ornamental low-relief sculptures on sections of the palaces with figurative scenes that recounted legends, commemorated historic battles and enhanced the power of the rulers. Many were narrative representations of specific historical events, motifs of "strong-names" representing the character of individual kings, and as mnemonic devices that allude to different traditions.[17](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-17-136876141)

The royal bas-relief tradition in its complete form likely dates to the 18th century during the reign of Agonglo and would have been derived from similar representations on temples, although most of the oldest surviving reliefs were made by the 19th century kings Gezo and Glele. Like the extensions of old palaces, and building of tombs and new soul-houses, many of the older reliefs were modified and/or added during the reigns of successive kings. Most were added to the two entry halls and protected from the elements by the high-pitched low hanging thatch roof which characterized Abomey's architecture.[18](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-18-136876141)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fcf2607e1-b67c-4c11-a9a1-2338fb71cc6b_1302x472.png)

_**Reliefs on an old Temple in Abomey**_, ca. 1940, Quai branly.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F680ec5a3-a516-457f-be34-e8caa2198ed5_912x564.png)

_**Bas-reliefs on the reception hall of king Gezo**_, ca. 1900. Metropolitan Museum of Art,

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fbf8c5cd7-6a55-4791-8a95-0e3975b88ef7_818x573.jpeg)

_**Reconstruction of the reception hall**_, ca. 1925, Quai branly

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F77659f46-8054-436c-aaf7-0f59240ab3fe_668x573.jpeg)

_**Bas-reliefs from the palace of King Behanzin**_, ca. 1894-1909, Quai branly

**Abomey in the 19th century from Gezo to Behanzin.**

Royal construction activity at Abomey was revived by Adandozan, who constructed his palace south of Agonglo's extension of Agaja's palace. However, this palace was taken over by his sucessor; King Gezo, who, in his erasure of Adandozan's from the king list, removed all physical traces of his reign. The reigns of the 19th century kings Gezo (r. 1818-1858) and Glele (r.1858-1889) are remembered as a golden age of Dahomey. Gezo was also a prolific builder, constructing multiple palaces and temples across Dahomey. However, he chose to retain Adandozan's palace at Abomey as his primary residence, but enlarged it by adding a two-story entrance hall and soul-houses for each of his predecessors.[19](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-19-136876141)

Gezo used his crowned prince’s palace and the area surrounding it to make architectural assertions of power and ingenuity. In 1828 he constructed the Hounjlo market which became the main market center for Abomey, positioned adjacent and to the west of his crowned prince’s palace and directly south of the royal palace. Around this market he built two multi-storied buildings, which occasionally served as receptions for foreign visitors.[20](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-20-136876141)

Gezo’s sucessor, King Glele (r. 1858-1889) constructed a large palace just south of Gezo's palace; the _Ouehondji_ (palace of glass windows). This was inturn flanked by several buildings he added later, such as the _adejeho_ (house of courage) -a where weapons were stored, a hall for the _ahosi_ (amazons), and a separate reception room where foreigners were received. His sucessor, Behanzin (r. 1889-1894) resided in Glele's palace as his short 3-year reign at Abomey couldn’t permit him to build one of his own before the French marched on the city in 1893/4.[21](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-21-136876141)

As the French army marched on the capital city of Abomey, Behanzin, realizing that continued military resistance was futile, escaped to set up his capital north. Before he left, he ordered the razing of the palace complex, which was preferred to having the sacred tombs and soul-houses falling into enemy hands. Save for the roof thatching, most of the palace buildings remained relatively undamaged. Behanzin's brother Agoli-Agbo (1894-1900) assumed the throne and was later recognized by the French who hoped to retain popular support through indirect rule. Subsquently, Agoli-Agbo partially restored some of the palaces for their symbolic and political significance to him and the new colonial occupiers, who raised a French flag over them, making the end of Abomey autonomy.[22](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-complete-history-of-abomey-capital#footnote-22-136876141)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5108f71d-93f4-4a87-8194-fa0c048ffd9f_760x464.png)

Section of Gezo’s Simbodji Palace, illustration from 1851.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F20e7daa2-062b-4154-b7fa-15a598778bfc_848x565.png)

Simbodji in 1894

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe82f83d5-c043-45b5-b82f-9c9fa401aa83_970x477.jpeg)

Simbodji in 1894-1909

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6a57af92-675b-4534-8801-916cea83eb37_1039x376.png)

_**Palace complex**_ in 1896, BNF.

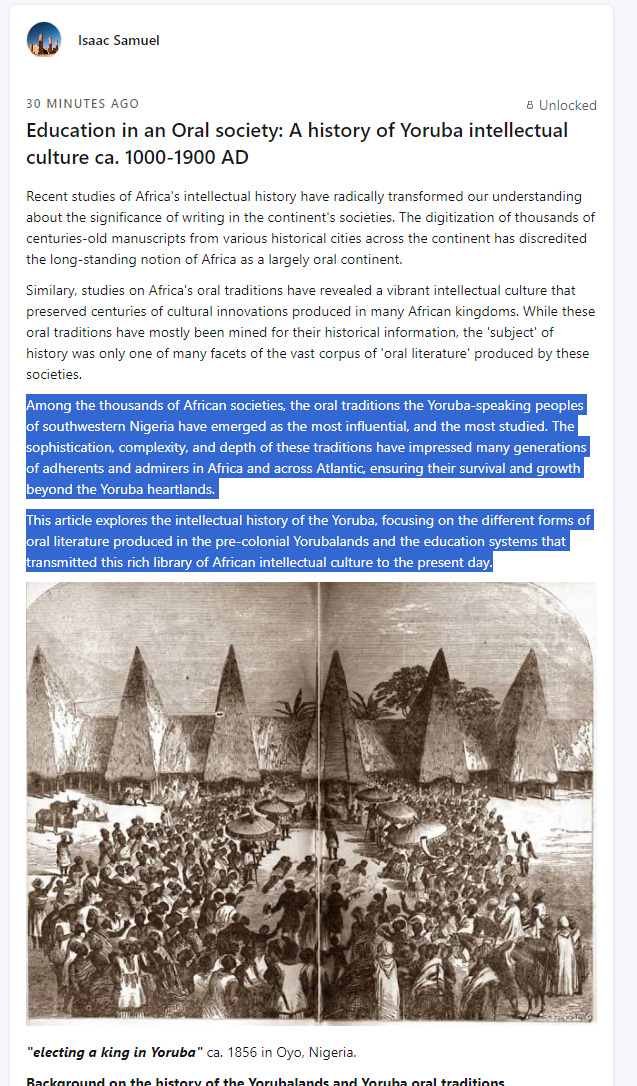

East of the kingdom of Dahomey was the Yoruba country of Oyo and Ife, two kingdoms that were **home to a vibrant intellectual culture where cultural innovations were recorded and transmitted orally**;

read more about it here in my latest Patreon article;

[EDUCATION IN AN ORAL SOCIETY](https://www.patreon.com/posts/88655364?pr=true)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F79abab6d-dc4e-4f86-ab4a-8d00c5911415_637x1086.png) | 2023-09-10T16:07:18+00:00 | {

"tokens": 10094

} |

A history of Women's political power and matriliny in the kingdom of Kongo. | In the 19th century, anthropologists were fascinated by the concept of matrilineal descent in which kinship is traced through the female line. | https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power | In the 19th century, anthropologists were fascinated by the concept of matrilineal descent in which kinship is traced through the female line. Matriliny was often confounded with matriarchy as a supposedly earlier stage of social evolution than patriarchy. Matriliny thus became a discrete object of exaggerated importance, particulary in central Africa, where scholars claimed to have identified a "matrilineal belt" of societies from the D.R. Congo to Mozambique, and wondered how they came into being.

This importance of matriliny appeared to be supported by the relatively elevated position of women in the societies of central Africa compared to western Europe, with one 17th century visitor to the Kongo kingdom remarking that _"the government was held by the women and the man is at her side only to help her"_. In many of the central African kingdoms, women could be heads of elite lineages, participate directly in political life, and occasionally served in positions of independent political authority. And in the early 20th century, many speakers of the Kongo language claimed to be members of matrilineal clans known as ‘Kanda’.

Its not difficult to see why a number of scholars would assume that Kongo may have originally been a matrilineal —or even matriarchal— society, that over time became male dominated. And how this matrilineal African society seems to vindicate the colonial-era theories of social evolution in which “less complex” matriarchal societies grow into “more complex” patriarchal states. As is often the case with most social histories of Africa however, the contribution of women to Kongo’s history was far from this simplistic colonial imaginary.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8598fe1d-9f97-49e7-8a9b-20249dcc18a2_666x566.png)

**Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this blog free for all:**

[PATREON](https://www.patreon.com/isaacsamuel64)

Scholars have often approached the concept of matriliny in central Africa from an athropological rather than historical perspective. Focusing on how societies are presently structured rather than how these structures changed through time.

One such prominent scholar of west-central Africa, Jan Vansina, observed that matrilineal groups were rare among the foragers of south-west Angola but common among the neighboring agro-pastoralists, indicating an influence of the latter on the former. Vansina postulated that as the agro-pastoral economy became more established in the late 1st millennium, the items and tools associated with it became highly valued property —a means to accumulate wealth and pass it on through inheritance. Matrilineal groups were then formed in response to the increased importance of goods, claims, and statuses, and hence of their inheritance or succession. As leadership and sucession were formalised, social alliances based on claims to common clanship, and stratified social groups of different status were created.[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-1-137752120)

According to Vansina, only descent through the mother’s line was used to establish corporate lineages headed by the oldest man of the group, but that wives lived patrilocally (ie: in their husband's residence). He argues that the sheer diversity of kinship systems in the region indicates that matriliny may have developed in different centers along other systems. For example among the Ambundu, the Kongo and the Tio —whose populations dominated the old kingdoms of the region— matrilineages competed with bilateral descent groups. This diverse framework, he suggests, was constantly remodeled by changes in demographics and political development.[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-2-137752120)

Yet despite their apparent ubiquity, matrilineal societies were not the majority of societies in the so-called matrilineal belt. Studies by other scholars looking at societies in the Lower Congo basin show that most of them are basically bilateral; they are never unequivocally patrilineal or matrilineal and may “oscillate” between the two.[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-3-137752120) More recent studies by other specialists such as Wyatt MacGaffey, argue that there were never really any matrilineal or patrilineal societies in the region, but there were instead several complex and overlapping forms of social organization (regarding inheritance and residency) that were consistently changed depending on what seemed advantageous to a give social group.[4](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-4-137752120)

Moving past contemporary debates on the existance of Matriliny, most scholars agree that the kinship systems in the so-called matrilineal belt was a product of a long and complex history. Focusing on the lower congo river basin, systems of mobilizing people often relied on fictive kinship or non-kinship organizations. In the Kongo kingdom, these groups first appear in internal documents of the 16th-17th century as political factions associated with powerful figures, and they expanded not just through kinship but also by clientage and other dependents. In this period, political loyalty took precedence over kinship in the emerging factions, thus leading to situations where rivaling groups could include people closely related by descent.[5](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-5-137752120)

Kongo's social organization at the turn of the 16th-17th century did not include any known matrilineal descent groups, and that the word _**'kanda**_' —which first appears in the late 19th/early 20th century, is a generic word for any group or category of people or things[6](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-6-137752120). The longstanding illusion that _**'kanda'**_ solely meant matrilineage was based on the linguistic error of supposing that, because in the 20th century the word kanda could mean “matriclan” its occurrence in early Kongo was evidence of matrilineal descent.[7](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-7-137752120) In documents written by Kongo elites, the various political and social groupings were rendered in Portuguese as _**geracao**_, signifying ‘lineage’ or ‘clan’ as early as 1550. But the context in which it was used, shows that it wasn’t simply an umbrella term but a social grouping that was associated with a powerful person, and which could be a rival of another group despite both containing closely related persons.[8](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-8-137752120)

In Kongo, kinship was re-organized to accommodate centralized authority and offices of administration were often elective or appointive rather than hereditary. Kings were elected by a royal council comprised of provincial nobles, many of whom were themselves appointed by the elected Kings, alongside other officials. The kingdom's centralized political system —where even the King was elected— left a great deal of discretion for the placement of people in positions of power, thus leaving relatively more room for women to hold offices than if sucession to office was purely hereditary. But it also might weaken some women's power when it was determined by their position in kinship systems.[9](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-9-137752120)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa1bafc76-fb25-49ac-a484-0d66584ecab5_696x557.png)

_**Aristocratic women of Kongo, ca. 1663, [the Parma Watercolors](https://mavcor.yale.edu/mavcor-journal/nature-culture-and-faith-seventeenth-century-kongo-and-angola).**_

[Share](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email&utm_content=share&action=share)

Kongo's elite women could thus access and exercise power through two channels. The first of these is appointment into office by the king to grow their core group of supporters, the second is playing the strategic role of power brokers, mediating disputes between rivalling kanda or rivaling royals.

Elite women appear early in Kongo's documented history in the late 15th century when the adoption of Christianity by King Nzinga Joao's court was opposed by some of his wives but openly embraced by others, most notably the Queen Leonor Nzinga a Nlaza. Leonor became an important patron for the nascent Kongo church, and was closely involved in ensuring the sucession of her son Nzinga Afonso to the throne, as well as Afonso's defeat of his rival brother Mpanzu a Nzinga.[10](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-10-137752120)

Leonor held an important role in Kongo’s politics, not only as a person who controlled wealth through rendas (revenue assignments) held in her own right, but also as a “daughter and mother of a king”, a position that according to a 1530 document such a woman _**“by that custom commands everything in Kongo”**_. Her prominent position in Kongo's politics indicates that she wielded significant political power, and was attimes left in charge of the kingdom while Afonso was campaigning.[11](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-11-137752120)

Not long after Leonor Nzinga’s demise appeared another prominent woman named dona Caterina, who also bore the title of '_**mwene Lukeni**_' as the head of the royal _**kanda**_/lineage of the Kongo kingdom's founder Lukeni lua Nimi (ca. 1380). This Caterina was related to Afonso's son and sucessor Pedro, who was installed in 1542 but later deposed and arrested by his nephew Garcia in 1545. Unlike Leonor however, Caterina was unsuccessful in mediating the factious rivary between the two kings and their supporters, being detained along with Pedro.[12](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-12-137752120)

In the suceeding years, kings drawn from different factions of the _lukeni_ lineage continued to rule Kongo until the emergence of another powerful woman named Izabel Lukeni lua Mvemba, managed to get her son Alvaro I (r. 1568-1587) elected to the throne. Alvaro was the son of Izabel and a Kongo nobleman before Izabel later married Alvaro's predecessor, king Henrique, who was at the time still a prince. But after king Henrique died trying to crush a _jaga_ rebellion in the east, Alvaro was installed, but was briefly forced to flee the capital which was invaded by the _jaga_s before a Kongo-Portugal army drove them off. Facing stiff opposition internally, Alvaro relied greatly on his mother; Izabel and his daughter; Leonor Afonso, to placate the rivaling factions. The three thereafter represented the founders of the new royal _**kanda**_/house of _kwilu_, which would rule Kongo until 1624.[13](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-13-137752120)

Following in the tradition of Kongo's royal women, Leonor Afonso was a patron of the church. But since only men could be involved in clerical capacities, Leonor tried to form an order of nuns in Kongo, following the model of the Carmelite nuns of Spain. She thus sent letters to the prioress of the Carmelites to that end. While the leader of the Carmelite mission in Kongo and other important members of the order did their best to establish the nunnery in Kongo, the attempt was ultimately fruitless. Leonor neverthless remained active in Kongo's Church, funding the construction of churches, and assisting the various missions active in the kingdom. Additionally, the Kongo elite created female lay associations alongside those of men that formed a significant locus of religiosity and social prestige for women in Kongo.[14](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-14-137752120)

As late as 1648, Leonor continued to play an important role in Kongo's politics, she represented the House of _kwilu_ started by king Alvaro and was thus a bridge, ally or plotter to the many descendants of Alvaro still in Kongo. One visiting missionary described her as _**“a woman**_ _**of very few words, but much judgment and government, and because of her sage experience and prudent counsel the king Garcia and his predecessor Alvaro always venerate and greatly esteem her and consult her for the best outcome of affairs"**_. This was despite both kings being drawn from a different lineage, as more factions had appeared in the intervening period.[15](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-15-137752120)

The early 17th century was one of the best documented periods in Kongo's history, and in highlighting the role of women in the kingdom's politics and society. Alvaro's sucessors, especially Alvaro II and III, appointed women in positions of administration and relied on them as brokers between the various factions. When Alvaro III died without an heir, a different faction managed to get their candidate elected as King Pedro II (1622-1624). Active at Pedro's royal council were a number of powerful women who also included women of the _Kwilu_ house such as Leonor Afonso, and Alvaro II's wife Escolastica. Both of them played an important role in mediating the transition from Alvaro III and Pedro II, at a critical time when Portugual invaded Kongo but was defeated at Mbanda Kasi.[16](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-16-137752120)

Besides these was Pedro II's wife Luiza, who was now a daughter and mother of a King upon the election of her son Garcia I to suceed the short-lived Pedro. However, Garcia I fell out of favour with the other royal women of the coucil (presumably Leonor and Escolastica), who were evidently now weary of the compromise of electing Pedro that had effectively removed the house of Kwilu from power. The royal women, who were known as “the matrons”, sat on the royal council and participated in decision making. They thus used the forces of an official appointed by Alvaro III, to depose Garcia I and install the former's nephew Ambrosio as king of Kongo.[17](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-17-137752120)

However, the _kwilu_ restoration was short-lived as kings from new houses suceeded them, These included Alvaro V of the _'kimpanzu'_ house, who was then deposed by another house; the ‘_kinlaza’_, represented by kings Alvaro VI (r. 1636-1641) and Garcia II (r. 1641-1661) . Yet throughout this period, the royal women retained a prominent position on Kongo's coucil, with Leonor in particular continuing to appear in Garcia II's court. Besides Leonor Afonso was Garcia II's sister Isabel who was an important patron of Kongo's church and funded the construction of a number of mission churches. Another was a second Leonor da Silva who was the sister of the count of Soyo (a rebellious province in the north), and was involved in an attempt to depose Garcia II.[18](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-18-137752120)

In some cases, women ruled provinces in Kongo during the 17th century and possessed armies which they directed. The province of Mpemba Kasi, just north of the capital, was ruled by a woman with the title of _'mother of the King of Kongo'_, while the province of Nsundi was jointly ruled by a duchess named Dona Lucia and her husband Pedro, the latter of whom at one point directed her armies against her husband due to his infidelity. According to a visiting priest in 1664, the power exercised by women wasn't just symbolic, _**"the government was held by the women and the man is at her side only to help her"**_. However, the conflict between Garcia II and the count of Soyo which led to the arrest of the two Leonors in 1652 and undermined their role as mediators, was part of the internal processes which eventually weakened the kingdom that descended into civil war after 1665.[19](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-19-137752120)

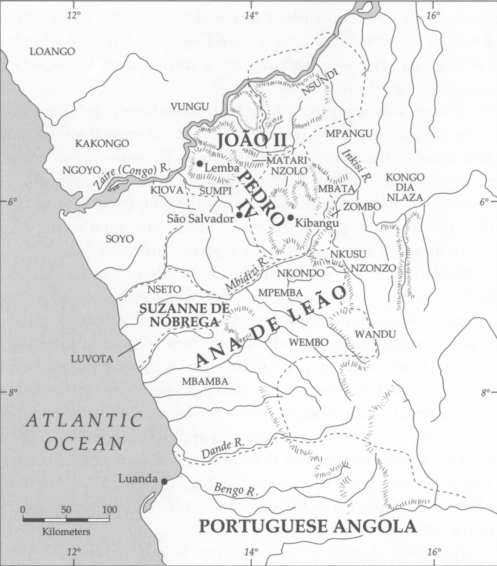

In the post-civil war period, women assumed a more direct role in Kongo's politics as kingmakers and as rulers of semi-autonomous provinces. After the capital was abandoned, effective power lay in regional capitals such as Mbanza Nkondo which was controlled by Ana Afonso de Leao, and Luvota which was controlled by Suzanna de Nobrega. The former was the sister of Garcia II and head of his royal house of _kinlaza_, while the latter was head of the _kimpanzu_ house, both of these houses would produce the majority of Kongo's kings during their lifetimes, and continuing until 1914. Both women exercised executive power in their respective realms, they were recognized as independent authorities during negotiations to end the civil war, and their kinsmen were appointed into important offices.[20](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-20-137752120)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdc1dab79-44d0-4827-8b85-8d012dcad5e5_497x566.png)

_**Map of Kongo around 1700.**_

The significance of Kongo's women in the church increased in the late 17th to early 18th century. Queen Ana had a reputation for piety, and even obtained the right to wear the habit of a Capuchin monk, and an unamed Queen who suceeded Suzanna at Luvota was also noted for her devotion. It was in this context that the religious movement led by a [princess Beatriz Kimpa Vita](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/one-womans-mission-to-unite-a-divided), which ultimately led to the restoration of the kingdom in 1709. Her movement further "indigenized" the Kongo church and elevated the role of women in Kongo's society much like the royal women had been doing. [21](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-21-137752120)

For the rest of the 18th century, many women dominated the political landscape of Kongo. Some of them, such as Violante Mwene Samba Nlaza, ruled as Queen regnant of the 'kingdom' of Wadu. The latter was one of the four provinces of Kongo but its ruler, Queen Violante, was virtually autonomous. She appointed dukes, commanded armies which in 1764 attempted to install a favorable king on Kongo's throne and in 1765 invaded Portuguese Angola. Violante was later suceeded as Queen of Wadu by Brites Afonso da Silva, another royal woman who continued the line of women sovereigns in the kingdom.[22](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-22-137752120)

Women in Kongo continued to appear in positions of power during the 19th century, albeit less directly involved in the kingdom's politics as consorts of powerful merchants, but many of them were prominent traders in their own right[23](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-23-137752120). Excavations of burials from sites like Kindoki indicate that close social groups of elites were interred in the same cemetery complex alongside rich grave goods as well as Christian insignia of royalty. Among these elites were women who were likely consorts or matriarchs of the male relatives buried alongside them. The presence of initiatory items of _kimpasi_ society as well as long distance trade goods next to the women indicates their relatively high status.[24](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-24-137752120)

It’s during this period that the matrilineal ‘kandas’ first emerged near the coastal regions, and were most likely associated with the commercial revolutions of the period as well as contests of legitimacy and land rights in the early colonial era.[25](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-25-137752120) The social histories of these clans were then synthesized in traditional accounts of the kingdom’s history at the turn of the 20th century, and uncritically reused by later scholars as accurate reconstructions of Kongo’s early history. While a few of the clans were descended from the old royal houses (which were infact patrilineal), the majority of the modern clans were relatively recent inventions.[26](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-26-137752120)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6d8348c2-d9fe-4495-82fe-074416d02150_712x505.png)

_**17th century illustration of Kongo titled “[Palm tree that gives wine”](https://mavcor.yale.edu/slice/palm-tree-gives-wine-october-may)**_, showing a woman with a gourd of palm wine. During the later centuries, women dominated the domestic trade in palm wine especially along important carravan routes in the kingdom.[27](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power#footnote-27-137752120)

[Share](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-womens-political-power?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email&utm_content=share&action=share)

The above overview of women in Kongo's history shows that elite women were deeply and decisively involved in the political and social organization of the Kongo kingdom. In a phenomenon that is quite exceptional for the era, the political careers of several women can be readily identified; ranging from shadowy but powerful figures in the early period, to independent authorities during the later period.

This outline also reveals that the organization of social relationships in Kongo were significantly influenced by the kingdom's political history. The kingdom’s loose political factions and social groups which; could be headed by powerful women or men; could be created upon the ascension of a new king; and didn't necessary contain close relatives, fail to meet the criteria of a historically 'matrilineal society'.

Ultimately, the various contributions of women to Kongo's history were the accomplishments of individual actors working against the limitations of male-dominated political and religious spaces to create one of Africa’s most powerful kingdoms.

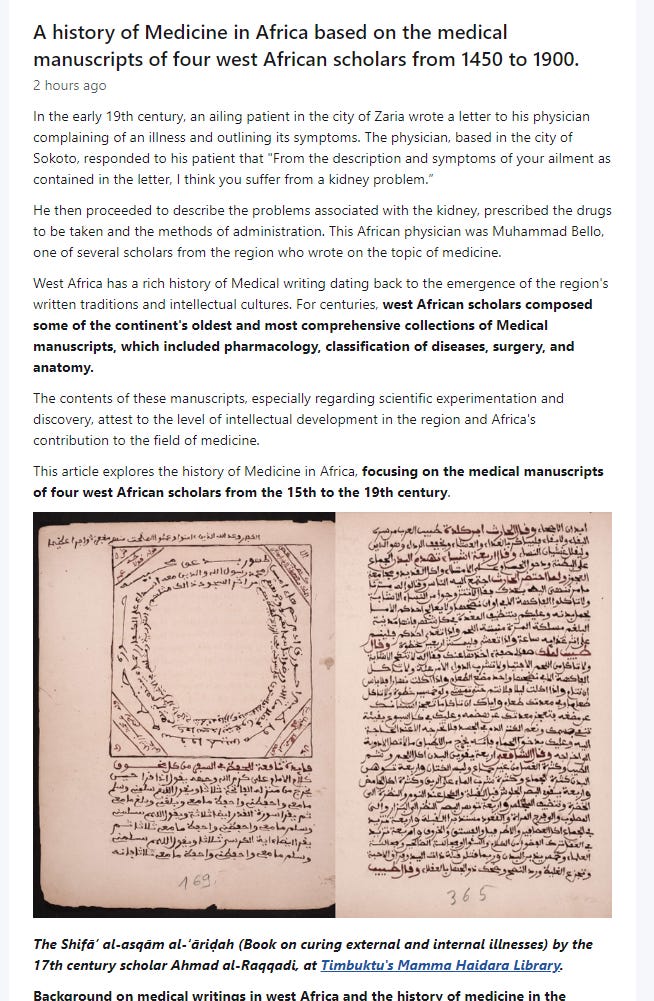

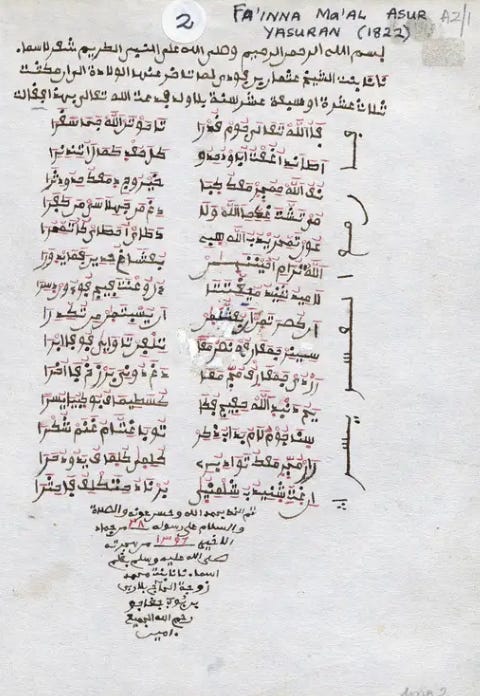

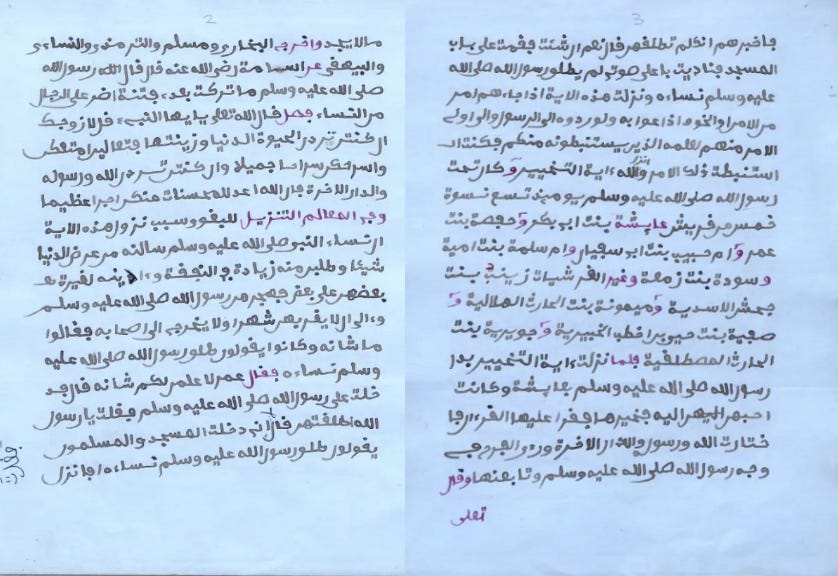

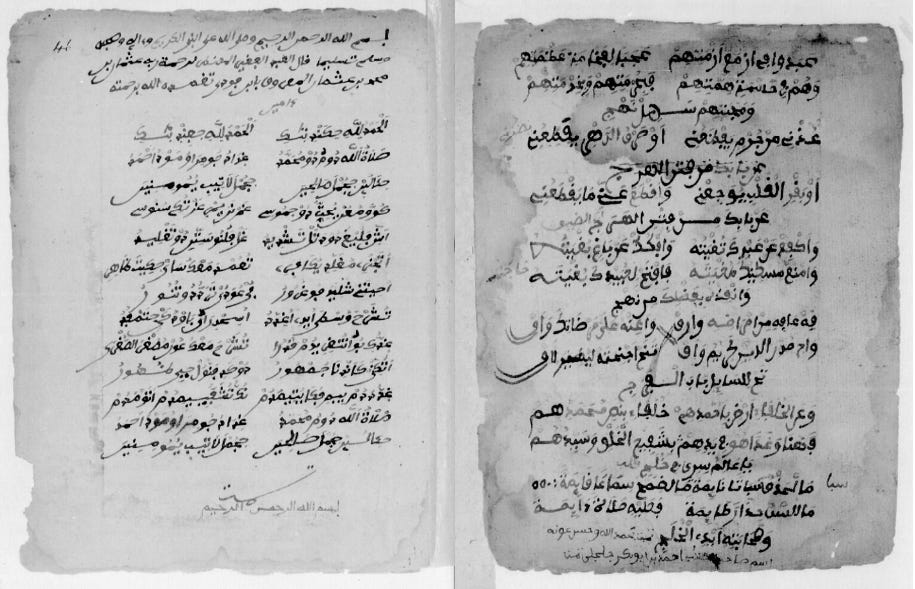

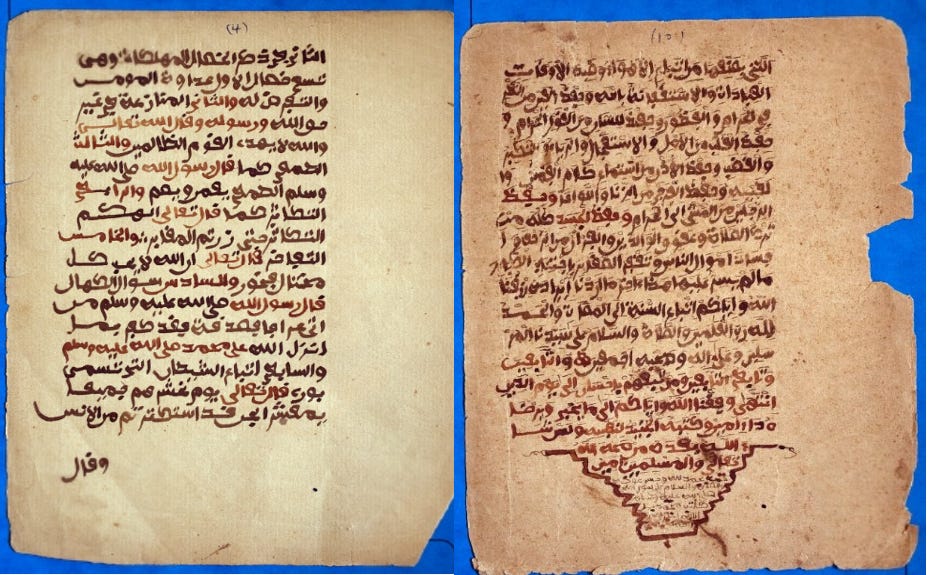

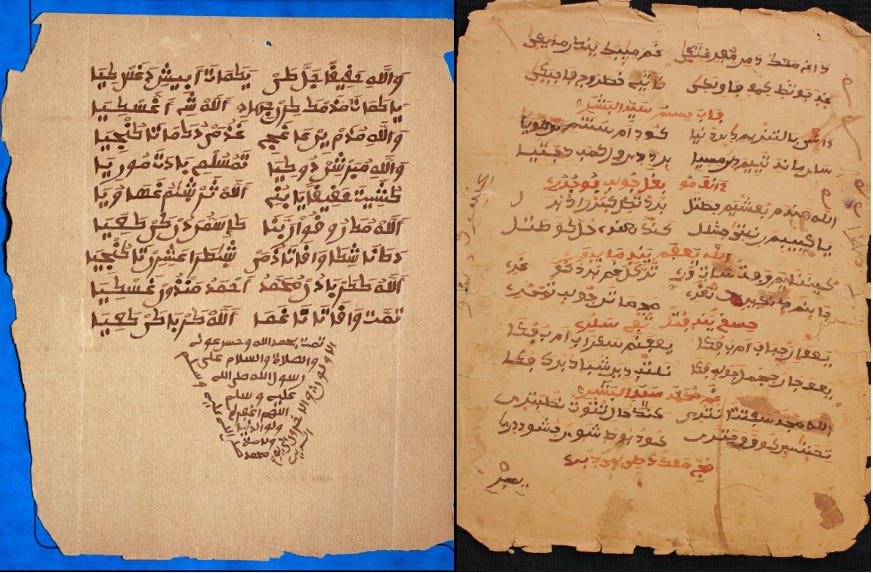

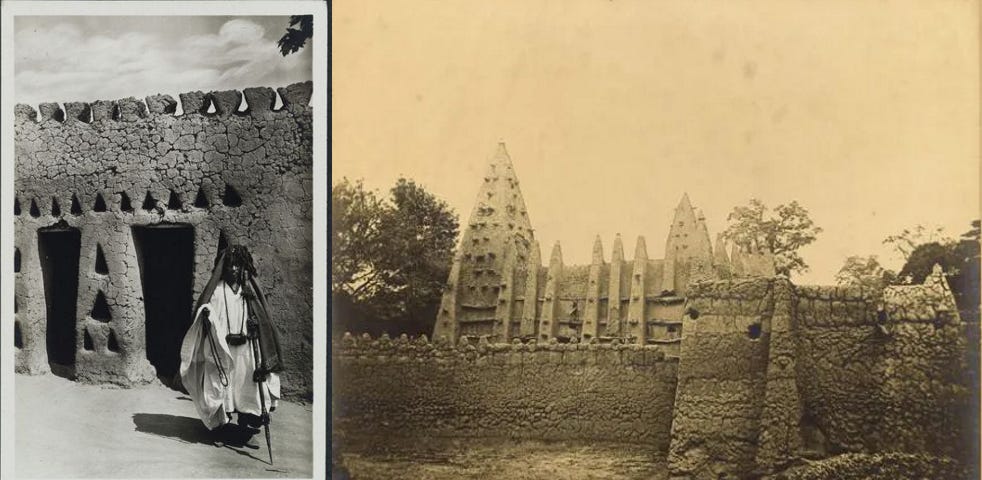

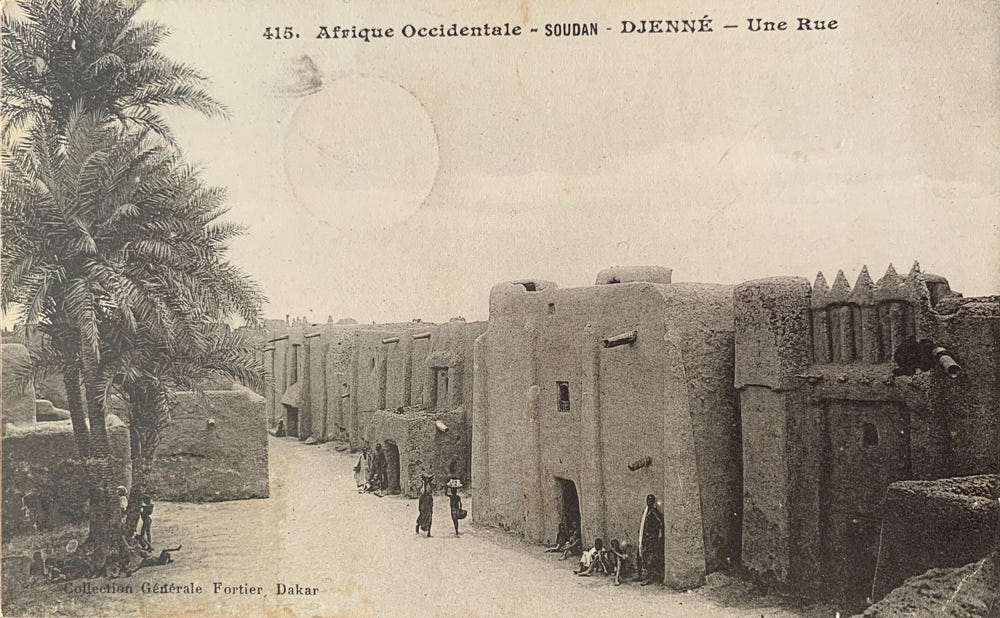

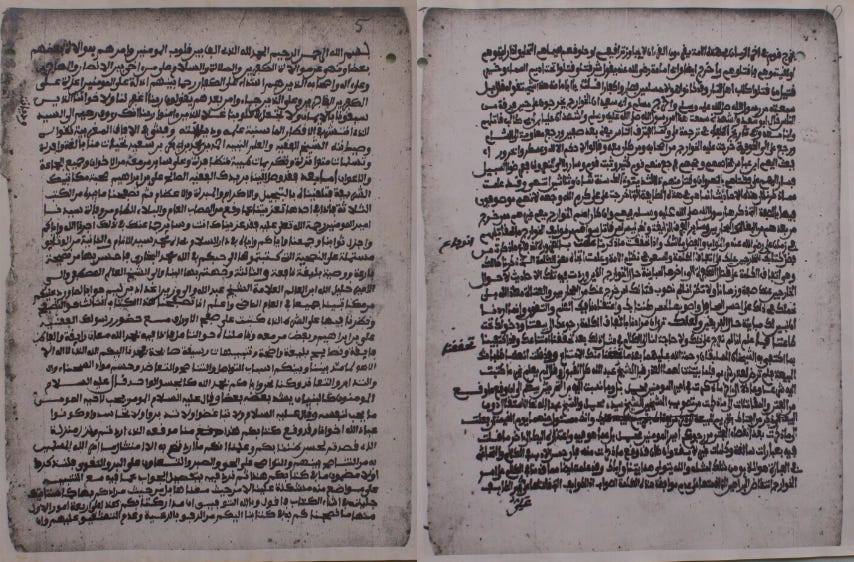

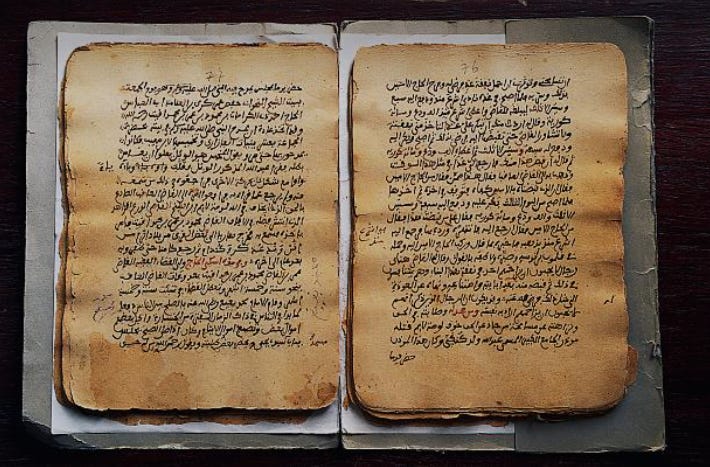

The ancient libraries of Africa contain many scientific manuscripts written by African scholars. **Among the most significant collections of Africa’s scientific literature are medical manuscripts written by west African physicians** between the 15th and 19th century.

**Read more about them here:**

[HISTORY OF MEDICINE IN AFRICA](https://www.patreon.com/posts/history-of-in-on-90073735)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa3148824-fad8-40e5-9044-16ed62cc4c6d_654x1001.png)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc5ee477e-1306-46af-857b-0c593e75c4d2_964x964.jpeg) | 2023-10-08T14:31:04+00:00 | {

"tokens": 6216

} |

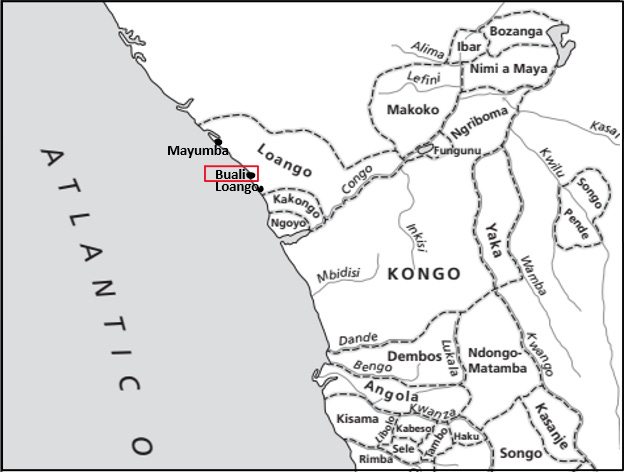

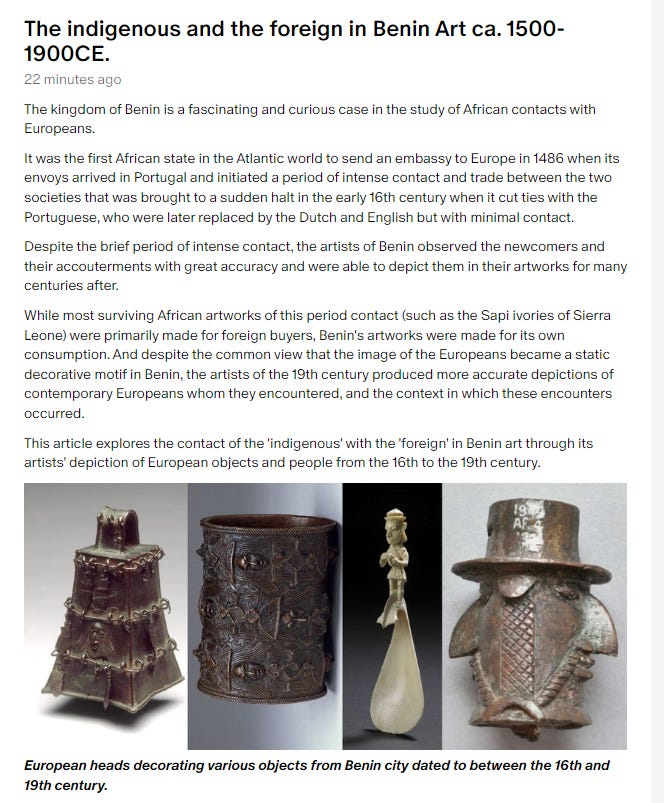

A history of the Loango kingdom (ca.1500-1883) : Power, Ivory and Art in west-central Africa. | Africa's past carved in ivory | https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500 | For more than five centuries, the kingdom of Loango dominated the coastal region of west central Africa between the modern countries of Gabon and Congo-Brazzaville. As a major regional power, Loango controlled lucrative trade routes that funneled African commodities into local and international markets, chief among which was ivory.

Loango artists created intricately carved ivory sculptures which reflected their sophisticated skill and profound cultural values, making their artworks a testament to the region's artistic and historical heritage. Loango ivories rank among the most immediate primary sources that offer direct African perspectives from an era of social and political change in west-central Africa on the eve of colonialism

This article explores the political and economic history of Loango, focusing on the kingdom's ivory trade and its ivory-carving tradition.

_**Map of west-central Africa in 1650 showing the kingdom of Loango**_

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fea1ef028-8254-43ec-8cf9-26acaef01d55_625x473.png)

**Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:**

[PATREON](https://www.patreon.com/isaacsamuel64)

**The government in Loango**

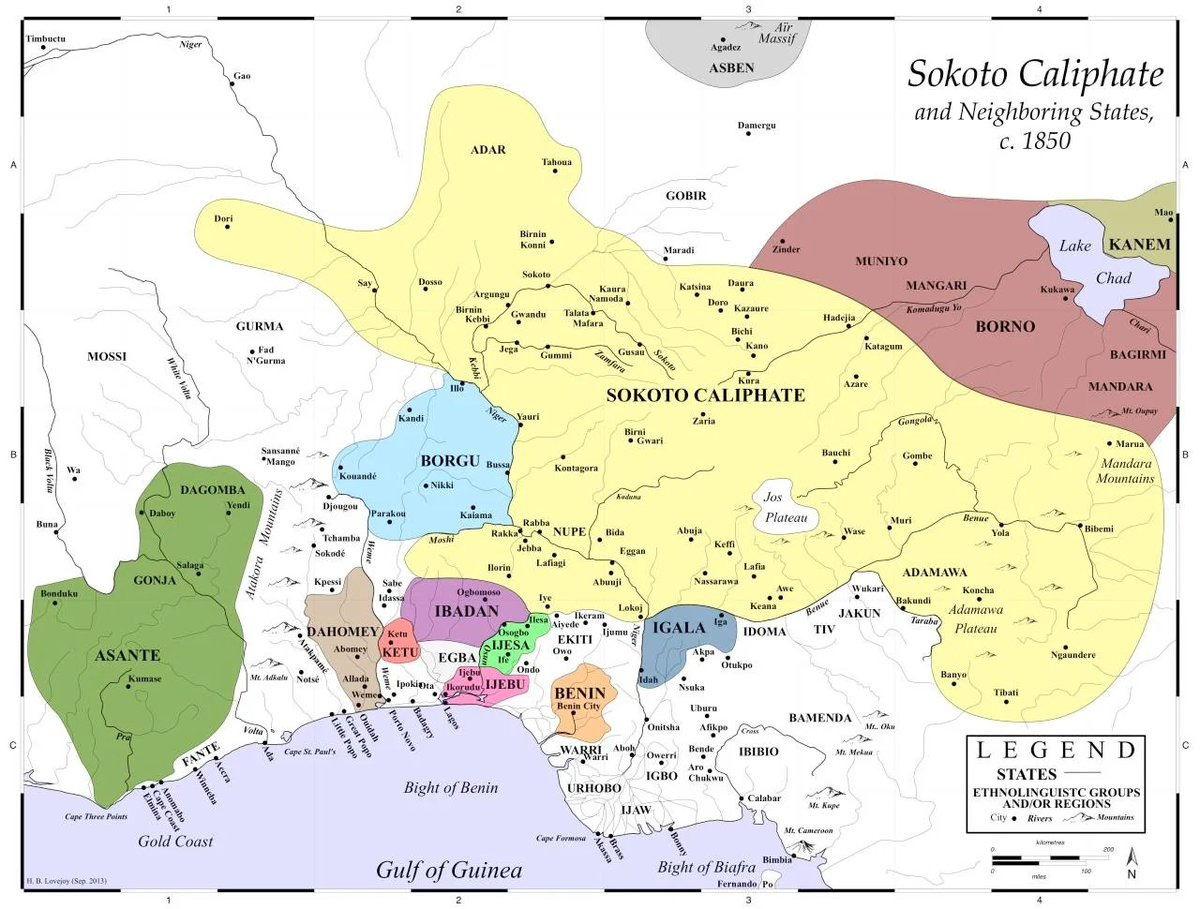

Beginning in the early 2nd millennium, the lower Congo river valley was divided into political and territorial units of varying sizes whose influence over their neighbors changed over time. The earliest state to emerge in the region was the kingdom of Kongo by the end of the 14th century, and it appears in external accounts as a fully centralized state in the 1480s. The polity of Loango would have emerged not long after Kongo's ascendance but wouldn't appear in the earliest accounts of west-central Africa.[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-1-119689450)

Loango was likely under the control of Kongo in the early 16th century, since the latter of which was nominally the suzerain of several early states in the lower Congo valley where its first rulers had themselves originated. Around the end of his reign, the Kongo king Diogo I (r. 1545-1561) sent a priest to named Sebastião de Souto to the court of the ruler of loango. Traditions documented in the 17th century credit a nobleman named Njimbe for establishing the independent kingdom of Loango.[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-2-119689450)

Njimbe built his power through the skillful use of force and alliances, conquering the neighboring polities of Wansi, Kilongo and Piri, the last of which become the home of his capital; Buali (_**Mbanza loango**_) near the coast. In the Kikongo language, a person from Piri would be called a _**Muvili**_, hence the origin of the term Vili as an ethnonym for people from the Kingdom of Loango[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-3-119689450). But the Vili "ethnicity" came to include anyone from the so-called Loango coast which included territories controlled by other states.[4](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-4-119689450)

Kongo lost any claims of suzerainty over Loango by 1584, as the latter was then fully independent, and had disappeared from the royal titles of Kongo's kings. In the 1580s, caravans coming from Loango regularly went inland to purchase copper, ivory and cloth. And increasing external demand for items from the interior augmented the pre-existing commercial configurations to the benefit of Loango, which extended its cultural and political influence along the coast as far as cape Lopez.[5](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-5-119689450)

Once a vassal of Kongo, Loango became a competitor of its former overlord as a supplier of Atlantic commodities. After the death of Njimbe in 1565, power passed to another king who ruled over sixty years until 1625. Loango had since consolidated its control over a large stretch of coastline, established the ports of Loango and Mayumba, and was expanding southward. The pattern of conquest and consolidation had given Loango a complex government, centered in a core province ruled directly by the king and royals, while outlying provinces remained under their pre-conquest dynasties who were supervised by appointed officials.[6](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-6-119689450)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe7d28453-2714-41a6-b8e0-803cb4c6c4f5_1962x1407.jpeg)

_**Colorized illustration of Olfert Dapper’s drawing of the Loango Capital, ca. 1686**_

By 1624, Loango expanded eastwards, using a network of military alliances to attack the eastern polities of Vungu and Wansi. These overtures were partly intended to monopolize the trade in copper and ivory in Bukkameale, a region that lay within the textile-producing belt of west-central Africa. This frontier region of Bukkameale located between Loango and Tio/Makoko kingdom, contained the copper mines of Mindouli/Mingole, and was the destination of most Vili carravans which regulary travelled through the interior both on foot and by canoe.[7](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-7-119689450)

The importance of Ivory, Cloth and Copper to Loango's rulers can be gleaned from this account by an early 17th century Dutch observer;

_**"**_\[The king\] _**has tremendous income, with houses full of elephant’s tusks, some of them full of copper, and many of them with lebongos**_ \[raphia cloth\]_**, which are common currency here… During my stay, more than 50,000 lbs.**_ \[of ivory\] _**were traded each year. … There is also much beautiful red copper, most of which comes from the kingdom of the Isiques**_ \[Makoko\] _**in the form of large copper arm-rings weighing between 1½ and 14 lb., which are smuggled out of the**_ \[Makoko\] _**country".**_[8](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-8-119689450)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F06e0ac8a-3d98-4719-9388-081b98cf92c0_431x677.png)

_**detail on a carved ivory tusk from Loango, depicting figures traveling by canoe and on foot. 1830-1887, No. TM-A-11083, Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen**_

Before the unnamed king's death in 1625, he instituted a rotation system of sucession in which each of the rulers of the four districts (Kaye, Boke, Selage, and Kabongo) within the core province would take the title of king. The first selected was Yambi ka Mbirisi from Kaye, who suceeded to the throne but had to face a brief sucession crisis from his rival candidates. The tenuous sucession system held for a while but evidently couldn't be maintained for long. In 1663, Loango was ruled by a king who, following a diplomatic and religious exchange with Kongo's province of Soyo, had taken up the name 'Afonso' after the famous king of Kongo.[9](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-9-119689450)

Afonso hoped his connection to Soyo would increase his power at the expense of the four other nobles meant to suceed him in rotation, since he’d expect to be suceeded by his sons instead. But this plan failed and Afonso was deposed by rival claimant who was himself deposed by another king in 1665. This started a civil war that ended in the 1670s, and when the king died, the rotation system was replaced by a state council (similar to the one in Kongo and other kingdoms), which elected kings. _**“they could raise one king up and replace him with another to their pleasure.”**_[10](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-10-119689450)

For most of the 18th century, the king's power was reduced as that of the councilors grew with each election. These councilors included the Magovo and the Mapouto who managed foreign affairs, the Makaka who commanded the army, the Mfuka who was in charge of trade, and the Makimba who had authority over the coast and interior. The king's role was confined to judicial matters such as resolving disputes and hearing cases.[11](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-11-119689450)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F511fed62-2c13-45c7-be6b-528f976f8c0e_561x670.png)

_**Detail of 19th century tusk, showing the emblem of the “Prime Minister of Loango ‘Mafuka Peter’” in the form of a coat of arms consisting of two seated animals in semi-rampant posture holding a perforated object between them. No. 11.10.83.2 -National Museums Liverpool.**_[12](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-12-119689450)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb9d33d51-99e9-4f99-8f17-5d84cb8a545f_794x599.jpeg)

_**“Audience of the King of Loango”, ca. 1756, Thomas Salmon**_

[Share](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email&utm_content=share&action=share)

After the death of a king, the election period often extended for some time while the country was nominally led by a 'Mani Boman' (regent) chosen by the king before his death. In 1701, no king had been elected despite the previous one having died nine months earlier, the kingdom was in the regency of Makunda in the interim. After the death of a king named Makossa in 1766, none was elected to succeed him in the 6 years that followed during which time the kingdom was led by two "regents". In 1772, Buatu was finally elected king, but when he died in 1787, no king was elected for nearly a century.[13](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-13-119689450)

From 1787 to 1870, executive power in Loango was held by the Nganga Mvumbi (priest of the corpse), another pre-existing official figure whose duty was to oversee the body of the king as he awaited burial. During the century-long interregnum, seven people holding this title acted as the leaders of the state. Their legitimacy lay in the claim that there was no suitable sucessor in the pool of candidates for the throne. The Nganga Mvumbi became part of the royal council which thus preserved its power by indefinitely postponing the election of the king. But the kingdom remained centralized in the hands of this bureaucracy, who exercised power in the name of the (deceased) king, collecting taxes, regulating trade, waging war and engaging with regional and foreign states.[14](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-14-119689450)

Descriptions of Loango in 1874 show a country firmly in the hands of the Nganga Mvumbi and his officers, although in the coastal areas, local officials begun to usurp official titles such as the Mafuk, which was sold to prominent families. New merchant classes also emerged among the low ranking nobles called the Mfumu Nsi, who built up power by attracting followers, dependents and slaves, as a consequence of increasing wealth from the commodities trade.[15](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-15-119689450)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1c2c8a20-f7bb-476b-b6b4-80f2c6377444_442x662.png)

_**detail of a 19th century Loango tusk depicting pipe-smoking figures being carried on a litter, No. TM-6049-29 -Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen**_

**External Ivory trade from Loango**

Loango, like most of its peers in central Africa had a mostly agricultural economy with some crafts industries for making textiles, iron and copper working, ivory and wood carving, etc. They had regular markets and used commodity currencies like cloth and copper and were marginally engaged in export trade. External trade items varied depending on demand and cost of purchase, but they primarily consisted of ivory, copper, captives, and cloth. These were acquired by private Vili merchants who were active in the segmented regional exchanges across regional trade routes, some extending as far as central Angola.[16](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-16-119689450)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F10ca3d45-ea9d-40c3-b5e7-c5888a1c3e8e_458x622.png)

_**detail on a 19th century Loango tusk depicting an elephant pinning down a hunter while another hunter aims a rifle at its head.**_ No. 96-28-1 _**\-**_Smithsonian Museum

The Vili's external trade was an extension of regional trade routes, no single state and no single item continuously dominated the entire region's external trade from the 16th to the 19th century. Cloth and salt was used as a means of exchange in caravans leaving Loango to trade in the interior. Among the goods acquired on these trade routes were ivory, copper, redwood and others. Most products were used for local consumption or intermediary exchange to facilitate acquisition of ivory and copper. Ivory was mostly acquired from the frontier regions, which were occupied by various groups including foragers ("pygmies"). The latter obtained the ivory using traps, and competitively sold it to both Loango and Makoko traders.[17](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-17-119689450)

The earliest external demand for Loango's ivory came from Portuguese traders. The Portuguese crown had attempted to monopolize trade between its own agents active along Loango's coast but this proved difficult to enforce as the Loango king refused the establishment of a Portuguese post in his region. This confined the Portuguese to the south and effectively edged them out of the ivory trade in favor of other buyers like the Dutch.[18](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-18-119689450)

Such was Loango's commitment to open trade that when the Dutch ship of the ivory trader Van den Broecke was captured by a Portuguese ship in 1608, armed forces from Loango intercepted the Portuguese ship, executed its crew and freed the Dutch prisoners.[19](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-19-119689450) The Portuguese didn't entirely abandon trade with loango, and would maintain a token presence well in to the 1600s. They also used other European agents as intermediaries. Eg from 1590-1610, the English trader Andrew Battell who had been detained in Luanda, visited Loango as an agent for the governor of Luanda. He mentions trading some fabric for three 120-pound tusks and cloth.[20](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-20-119689450)

The Dutch become the most active traders on the Loango coast beginning in the early 17th century. The account of the Dutch ivory trader Pieter van den Broecke who was active in Loango between 1610 and 1612 provides some of the most detailed descriptions of this early trade. Broecke operated trading stations in the ports of Loango and Maiomba, where he specialized in camwood, raffia cloth and ivory, items that were cheaper and easier to store than the main external trade of the time which was captives. The camwood (used for dyeing cloth) and the raffia cloth (used in local trade) were mostly intermediaries commodities used to purchase ivory.[21](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-21-119689450)

Broecke and his agents acquired about 311,000 pounds of ivory after several trading seasons in Loango across a 5-year period. Most of the ivory came from private traders in the kingdom with a few coming from the Loango king himself. At the same time, Loango continued to be a major exporter of other items including cloth called makuta, of which up to 80,000 meters were traded with Luanda in 1611.[22](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-22-119689450)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fed00d656-d491-4921-88ff-f2f891cf95dd_599x386.jpeg)

_**work made by ivory carvers in Loango, ca. 1910**_

The Dutch activities in Loango must have threatened Portuguese interests in the region, since the kings of Kongo and Ndongo sucessfully exploited the Dutch-Portuguese rivalry for their own interests. In 1624 the Luanda governor Fernão de Souza requested the Loango King to close the Dutch trading post, in exchange for buying all supplies of ivory, military assistance and a delegation of priests. But the Loango king rejected all offers, and continued to trade with the Dutch.[23](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-23-119689450)

Loango's ivory exports continued in significant quantities well into the late 17th century, but some observers noted that the advancement of the ivory frontier inland. Basing on information received from merchants active in Loango, the Ducth writer Olfert Dapper indicated that by the 1660s, supplies of ivory at the coast were decreasing because of the great difficulties in obtaining it.[24](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-24-119689450)

The gradual decline in external ivory trade coincided with the rise in demand of slaves.[25](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-25-119689450) In the last decades of the 17th century, the Loango port briefly became a major embarkation point for captives from the interior, as several routes converged at the port.[26](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-26-119689450) But Loango's port was soon displaced by Malemba, (a port of Kakongo kingdom) and later by Cabinda (a port of Ngoyo kingdom) in the 18th century, and lastly by Boma in the early 19th century, the first three of which were located on the so-called 'Loango coast'. Mentions of Loango in external accounts therefore don't exclusively refer to the kingdom, anymore than 'the bight of Benin' refers to areas controlled by the Benin kingdom.[27](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-27-119689450)

External Ivory trade continued in the 18th century, with records of significant exports in 1787, and the trade had fully recovered in the 19th century as the main export of Loango and its immediate neighbors after the decline of slave trade. The rising demand for commodities such as palm oil, rubber, camwood and ivory, reinvigorated established systems of trade and more than 78 factories were established along Loango's coast. Large exports of ivory were noted by visitors and traders in Loango and the kakongo kingdoms as early as 1817 and 1820, especially through the port of Mayumba.[28](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-28-119689450)

Vili carravans crossed territorial boundaries in different polities protected by toll points, and shrines with armed escorts provided by local rulers. Rising prices compensated the distances and capital invested by traders in acquiring the ivory whose frontier continued to expand inland. The wealth and dependents accumulated by the traders and the 'Mafuk' authorities at the coast gradually eroded the power of the central authorities in the capital. Factory communities created new markets for Vili entrepreneurs including ivory carvers who found new demand beyond their usual royal clientele. Its these carvers that created the iconic ivory artworks of Loango.[29](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-history-of-the-loango-kingdom-ca1500#footnote-29-119689450)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F89b9ec82-7e3a-4792-be31-6c3f74b703c4_630x620.png)

Detail on a carved ivory tusk from Loango, ca. 1890, No. 71.1973.24.1 -Quai branly, depicting a European coastal ‘factory’

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F087c069c-5cd2-4012-b775-36a0a60440cb_862x556.png)

_**Carved ivory tusk from Loango, ca. 1906, No. IIIC20534, Berlin Ethnological Museum**_. depicting traders negotiating and giving tribute, and a procession of porters carrying merchandise.

**The Ivory Art tradition of Loango**

The carving of ivory in Loango was part of an old art tradition attested across many kingdoms in west central Africa.